A year ago, I hoped that I would be starting this semester with a project on mountaintop removal, creating a piece to be shown in a student concert that would build one segment of what would eventually become my senior thesis. I had been dreaming of this piece since freshman year when I first went to West Virginia and saw mountaintop removal sites in person. Due to Covid-19 restrictions, I no longer felt that it was possible to build that piece. Or at least it wasn’t the right moment to do it given how much I felt would be lacking if none of the dancers could come within six feet of each other. But, I still felt a need to create something or at least be a part of a process that was creating something. The main goal of starting this process was to help me figure out ways to keep moving forward even when I don’t feel creative. I wanted to discover things that would help me sustain my practice of creating dances through the ups and downs of life. Once I started the process, a lot of other important ideas emerged as well like levels of authority, response to the environment, and listening to what is in the room.

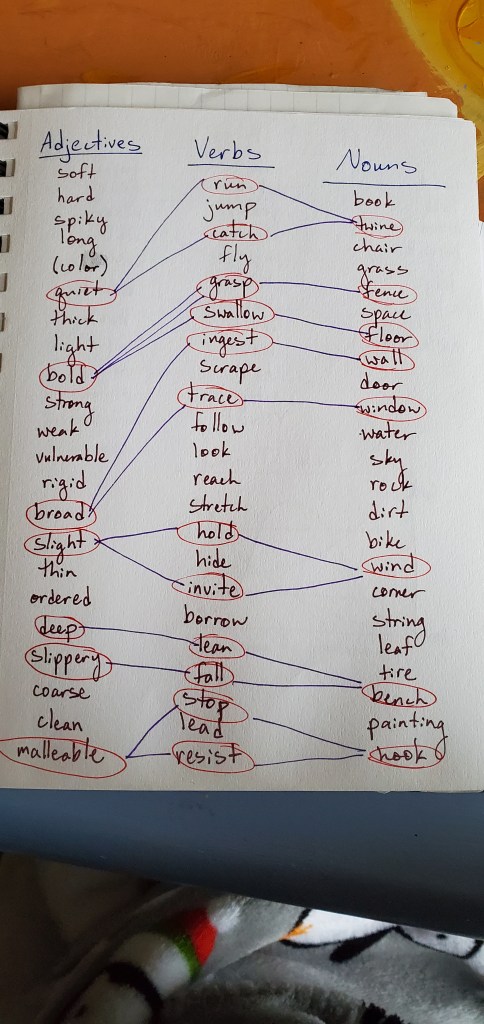

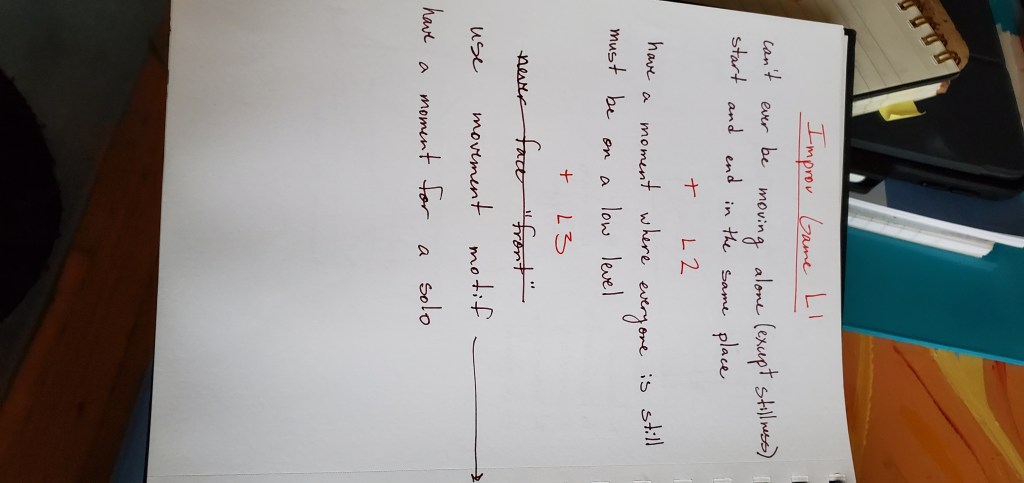

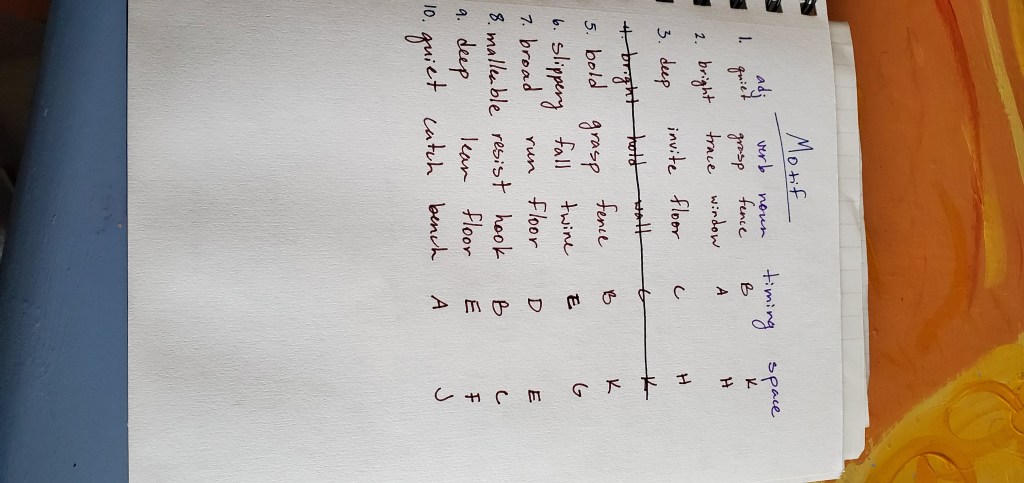

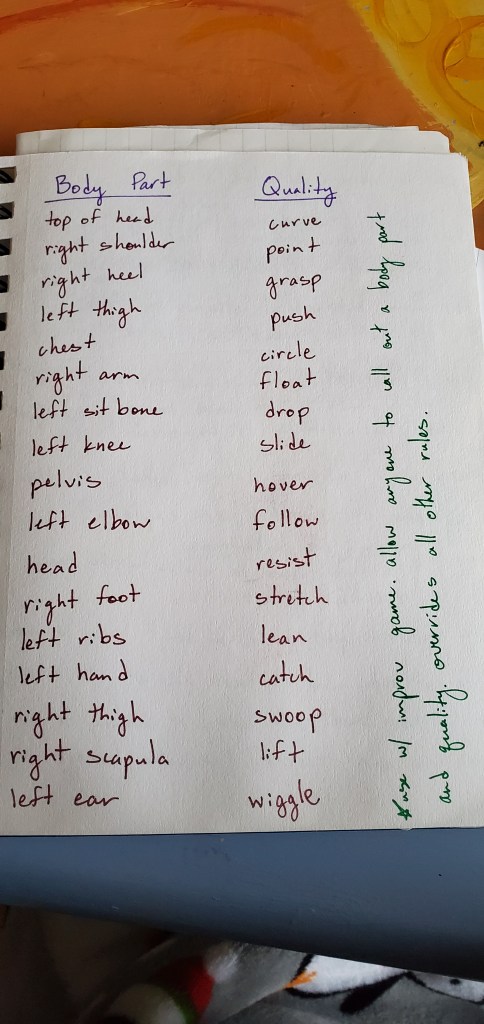

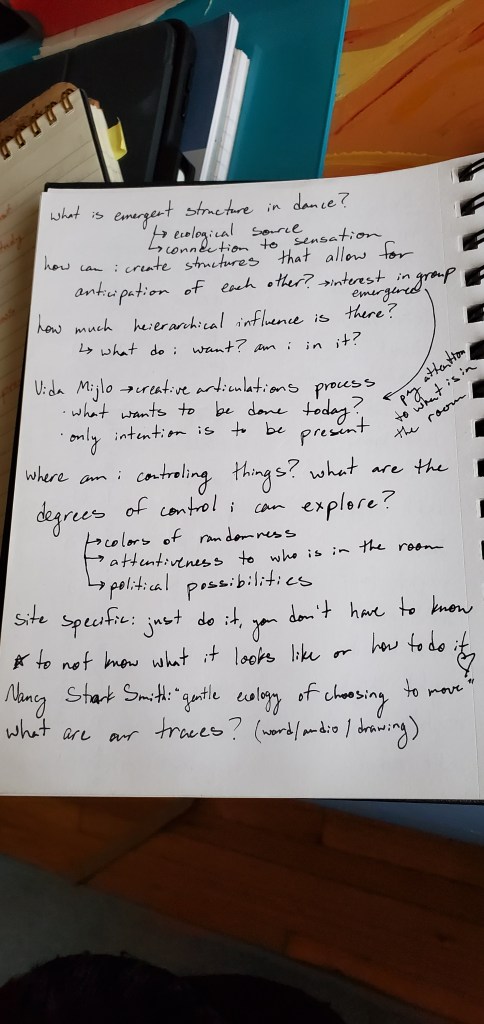

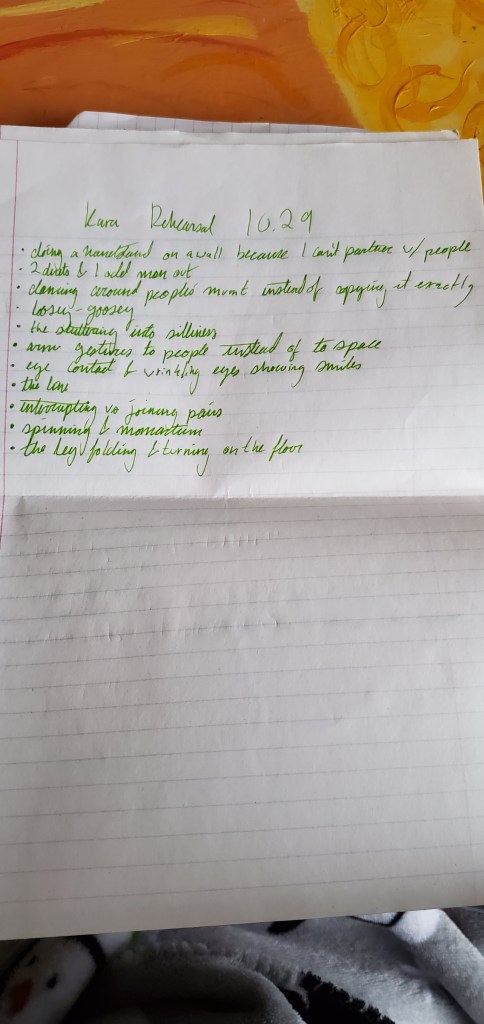

I started out with structures that I was already familiar with that I could use to create material quickly and with little effort. I used randomized nouns, verbs, and adjectives, as well as spatial designs and timing patterns to create a score for a phrase of movement. My original plan was that I was going to be the objective choreographer and all of the dancers would help me generate material, so while the score was randomized, I still had a lot of control over the process. I also created a set of random body parts from which to make duets and a random list of body parts and qualities that could be used to make another phrase. For the first few rehearsals, we entered the space together and checked in using an activity I borrowed from Gina Hoch-Stall: going around in a circle, each person does a movement that feels good in their bodies and everyone else mirrors them while they answer a question about their day or their state of mind. Then, I would pick up my notebook and lead them through one of the movement generating processes that I had planned out. We created a solo for everybody that was based on the same score so that while each person’s movement was different, there was something really striking about everyone moving with the same nuances in timing and level in space. We also created three duets this way off of the same score so each one was unique but used the same inspiration of trading energy while not touching. These chance procedures were really fruitful for movement generation and created some really interesting results without requiring me to envision it first.

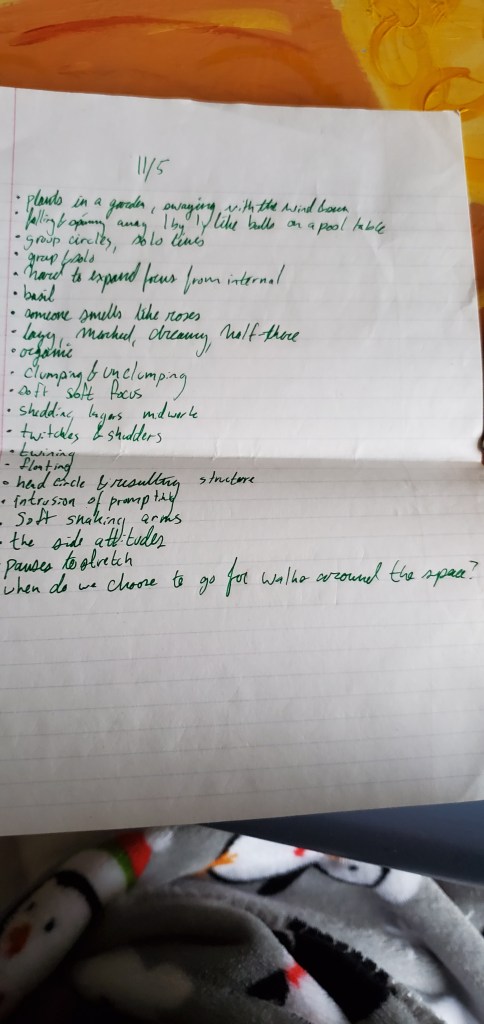

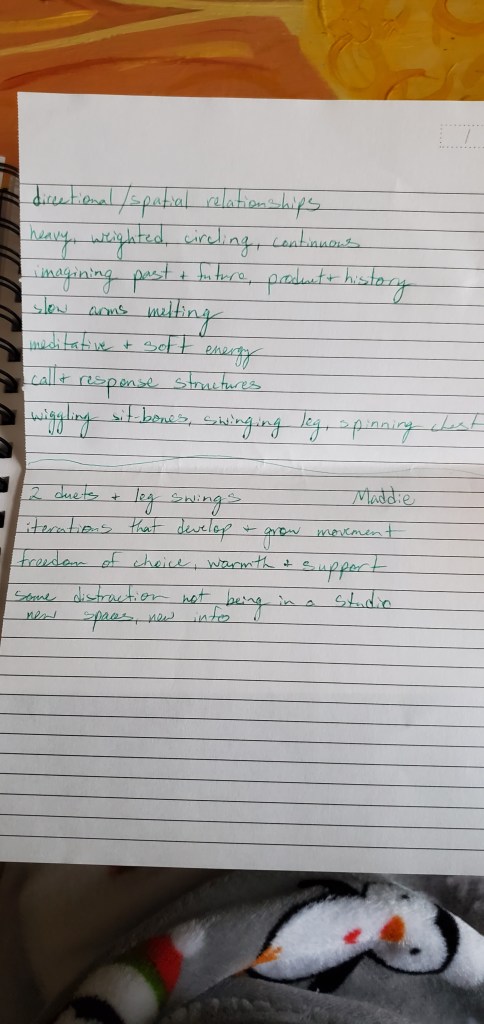

Flip through the notebook I used to outline our process:

Take a look at what we created:

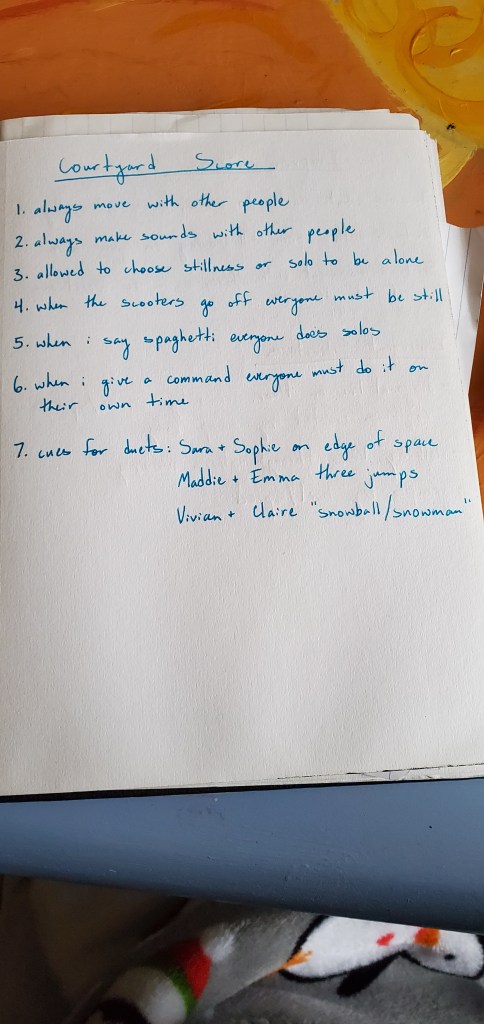

At this point I was able to have a meeting with my advisor, Norah Zuniga-Shaw, who challenged me to go beyond my own preconceptions of the process. With her guidance, I decided to start changing how I was part of the group and redistributing some of the control to other members. This is where the project started to shift from creating material, to creating experiences. We experimented with going outside and developing scores as a group rather than me writing them down beforehand. We even changed the use of some of my written scores and created new rules to govern our experience. Going outside introduced new factors from the environment around us into the process. We used the clock tower to time our improvisation at one point and during another iteration we used the alarm on a Lime Scooter to trigger pauses in our dance. This opened me up to the possibilities that the environment can contribute to an experience.

Listen to some of our outdoor experiments:

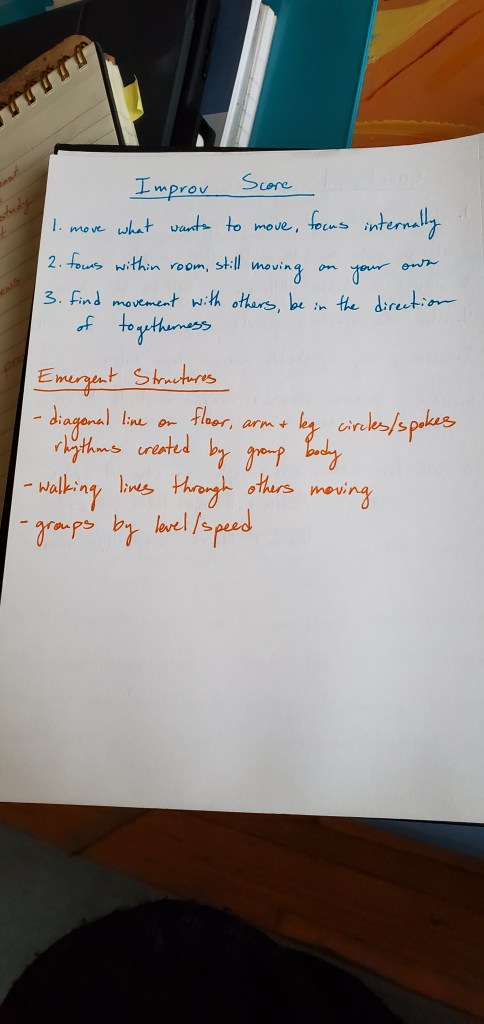

The last few rehearsals we had to come back inside because it was getting colder and there was one last part of the process that we hadn’t spent much time with, but that seemed to be an integral part of what was happening. One of the rules that had been constant is that “nobody can ever be alone.” If one person starts moving, someone else needs to move with them and you can never be moving alone, with a few exceptions depending on the score. It was the responsibility of the group as a community to make sure that nobody was ever alone. At the core of this was the basic idea of “moving what wants to be moved” which is usually what started off the improvisation. To explore this idea deeper, for the last three rehearsals we did a 40 minute improvisation. For the first 10 minutes we would focus on only moving what wanted to be moved in our bodies and keep our focus internal. For the second 10 minutes we would continue moving only what wanted to be moved but we would allow our focus to extend into the room and be aware of what other people were doing. For the last 20 minutes we would “move in the direction of togetherness” by allowing ourselves to follow the rule that had been used in previous experiments but not being too precious about it. This process was the most healing and enjoyable to take part of. As a group everybody came out of it feeling connected to each other and there were always some really beautiful structures that emerged from the improvisation without us having to force anything. This part of the process opened up the possibilities that little control and very few guidelines could provide to a group improvisational experience.

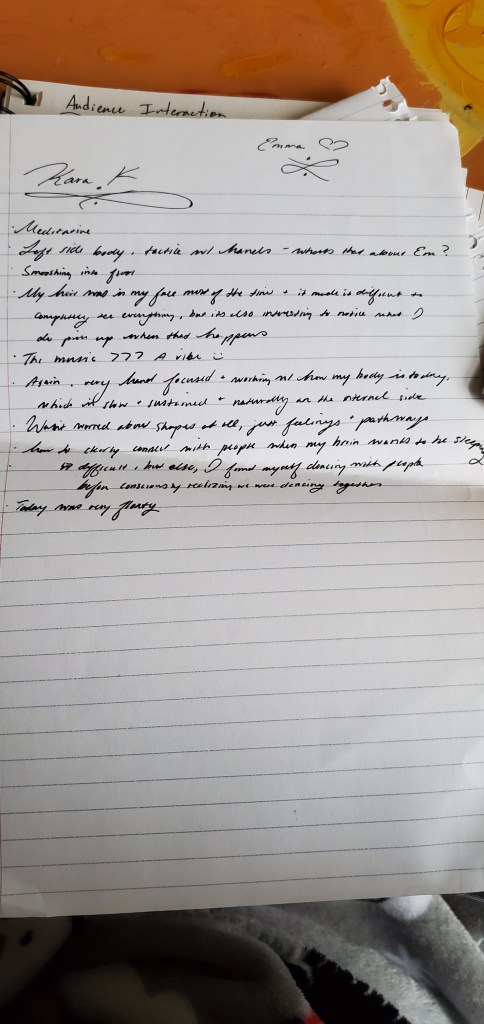

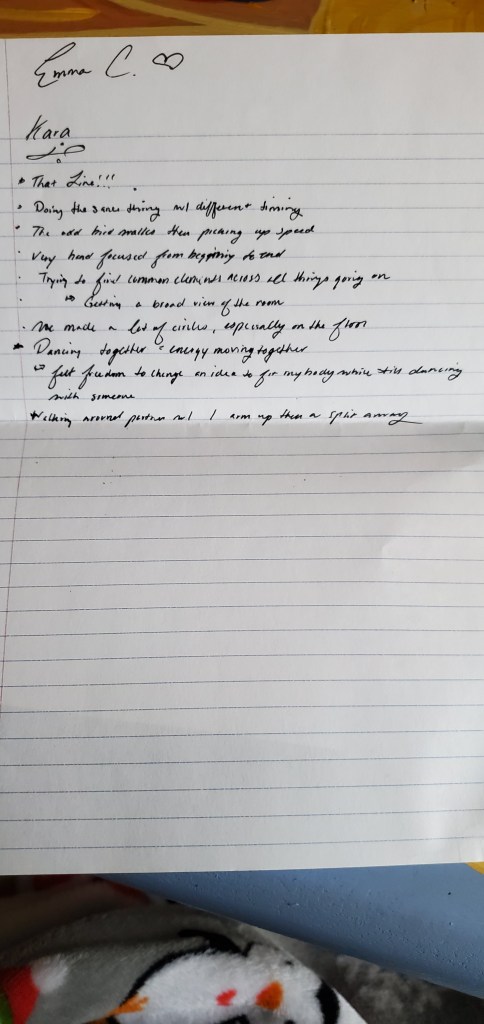

Read the reflections from the group on our improvisational experiences:

At the conclusion of the process, I submitted a video to the Virtual Student Showcase presented by the Ohio State University Department of Dance that highlighted the gems of this process and provided space for viewers to experience some of it themselves. As a whole this process fulfilled its original goal of helping me create even when I am not necessarily inspired to do so, and I was able to discover tools that can help curate choreographic and improvisational experiences in the future.